Vote, Post, Repeat: On Performative Progressivism and the Politics of Convenience

We owe nothing to the state, but everything to each other.

So, did you vote in the April federal elections? Maybe you did. It was supposed to be "the most important election of our lifetime ". A second question, then. What are your relations, responsibilities, and obligations?

These are anchoring questions for those who use the languages of progressivism, left politics, or community organizing when engaging with electoralism. Especially those who crib the language, such as those who have mutated the meaning of harm reduction to apply it to electoral politics.

I speak and write in many directions, intending to create a throughline about the imperative to honour our relations in a way that resonates and aligns with our politics and the world we want to build. With this piece, I attempt to hold space for the complexity of navigating settler systems without collapsing into their logics — and to weave in the kind of fierce clarity, principled refusal, and deep love that runs through the work of those who have taught me and will continue to do so.

These days, I am aware of the weight that many of us carry: the tension between participating in systems we do not believe in and our ongoing responsibility to one another beyond such systems. Here, decisions are made and responsibilities rendered. If you voted and claimed it was in the name of social justice, there is a reckoning to be had—a need to confront the contradictions between that choice and the systems it upholds.

The result of these attempts to grapple with the theories and practices of electoralism has made me reflect not just on the act of voting, but it has also reminded me that our politics, ethics, and solidarities must be rooted elsewhere. I think of Rudy's Accomplices Not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex. Our politics must be rooted in our relations, not institutions. In our actions, not our comfort. In our commitments, not our compliance.

When Language Travels

A few months ago, I had a small picnic with some friends from different walks of life, who now all organize together around arts and liberation. As we sat in Montréal's Little Portugal Park in the dark, sharing snacks, we began discussing the upcoming elections and wondered how, after 18 months of consciousness-raising, so much still remained that didn't make sense to us.

We talked about how people—regardless of how performative they were or how fluently they spoke the language of theory and liberation—were now, in this moment of elections, claiming to be doing grassroots community organizing or some iteration of it. However, in practice, what many of them were doing looked exactly like what their conservative counterparts were doing: canvassing, door-to-door campaigning, putting up signs, and mapping constituents.

We found ourselves asking: How is it that, despite all the language, theory, and performative politics, so many people were now claiming to engage in grassroots organizing—when, in practice, their actions mirrored those of conservative campaigns?

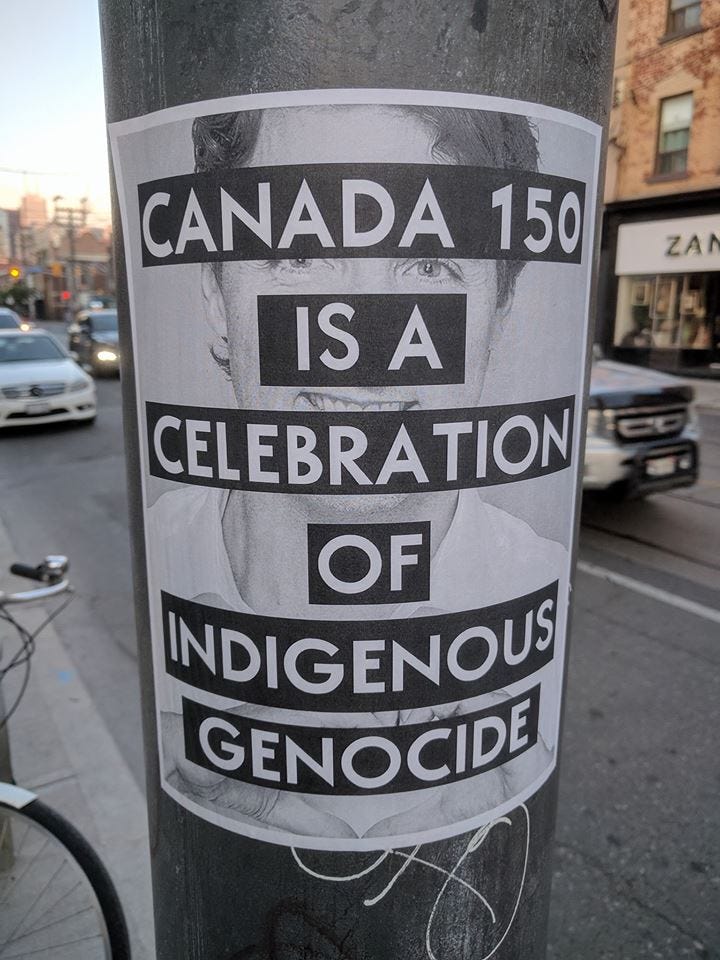

Art by Jay Soule aka CHIPPEWAR, Jay creates art under the name Chippewar which represents the hostile relationship that Canada's native people's have with the government of the land they have resided in since their creation.

Canvassing, door-to-door campaigning, putting up signs, and mapping out constituents—these are standard electoral tactics. When conservatives engage in them, we don't call it community organizing. However, when progressives engage in similar actions, there is often a desire to reframe these actions as inherently righteous or transformative—as if proximity to progressive values automatically changes the nature of the work, rendering it more righteous. It's like trying to force the sticky, messy batter of electoral politics—full of contradictions and compromises—into the mold of grassroots, community-built activism. But it just doesn't fit.

There is a tendency among social democrats and those newly identifying with the left to convince themselves that all the work they do is inherently radical or community-based. This often results in an insistence on attaching liberatory language—like "harm reduction"—to every political act, including electoral participation. We saw this clearly in the framing of voting as a moral imperative: campaigns proliferated that attempted to circle the square, promoting voting as a way to "do good" and offset systemic harm. But this logic often falls apart—it feels like throwing one's ballot into a pool of blood and hoping it cleanses something.

The Vote for Palestine campaign, while admirable and a meaningful intervention, existed within this complex tension. Its call for a two-way arms embargo and for Canada to recognize a Palestinian state was endorsed by only ten percent of incoming Liberal MPs—revealing a limit of moral persuasion in electoral politics. While the campaign is an important step, critics have pointed out that electoral strategies alone cannot deliver justice. In a media environment hostile to Palestinian liberation, these limitations risked overshadowing the broader goals of the campaign. That's why it is crucial to mobilize the growing number of people of conscience who are signing the anti-genocide pledge and organizing beyond the ballot box. The escalation of terror continues in Gaza, with The United Nations having declared that 14,000 babies could die within days if thousands of trucks filled with aid, including baby food, do not make it to Gazans. The situation continues to grow dire. We have to diversify on the ground beyond an electoral mindset.

While many still insist on viewing elections as a redemptive ritual of democracy, it's crucial to remain critical of what we're being asked to participate in and who we're being asked to trust. As scholar and writer Steven Salaita warns, "Be careful about nostalgia for a democratic polity that never was. Be careful about activists and organizations appended to the Democratic Party. Be careful about the podcasters who built an audience by caping for Bernie Sanders… Be careful about the next shiny young politician who comes out of nowhere to save us… Be careful about anything that tries to make a place for oppression in this world."

Salaita's words, though directed at U.S. audiences, resonate deeply in the Canadian context, where similar dynamics play out under the guise of multicultural tolerance and liberal benevolence. Here, too, activists are pressured to align with political parties that ultimately uphold settler-colonial logics; celebrities and influencers posture as progressive while soft-pedalling genocide; and electoral politics are held up as the only legitimate site of change. Others adopt activist language solely in corporate settings. What is all this rhetoric worth if it is constantly being used to channel our resources into institutions that were never designed to serve emancipatory aims. We are told to place our faith in institutional mechanisms that have consistently failed Black, Indigenous, and racialized communities—especially those who organize for Palestinian liberation. "Being careful" in this context must mean more than cautious participation. It must mean cultivating a discerning political practice that refuses to accommodate oppression under any banner, no matter how progressive it claims to be.

Attempting to take the dough of electoral politics to grow activism is like trying to make muffins out of pancake mix — the ingredients might seem familiar, but the structure, the intention, the outcome? Entirely different. Grassroots work rises in its own way. Electoral politics flattens it.

Electoral politics and grassroots activism may share some language (primarily due to the spread of DEI policy throughout workplaces via graduate-educated facilitators), but they don't speak the same dialect. One is built for containment, while the other is built for transformation.

Trying to cook with the messy batter of electoral politics is bound to fail. It is full of contradictions, compromises, and half-baked agendas. It cracks. It buckles. It was never meant to hold the fire of activism. Electoralism is a recipe built for repetition, not resistance.

After more than 20 months of consciousness-raising—and an endless stream of images that should haunt any feeling human—we are now being told that voting is the ultimate use of our voice. That to vote is to contest genocide. That voting is a radical act. It is framed as something big, moral, and novel—yet also as something simple, a 20-minute task. A routine part of being Canadian, without much critical examination of what "being Canadian" means or how inclusion in Canada hinges on others being excluded from it.

Elbows Up, Flags Out – Red, White, and Complicit: The New Face of Canadian Nationalism

In the context of the recent federal election, an overt evocation of "Canada First" sentiment has emerged—not just from the political right but also within the rhetoric of the New Democratic Party (NDP). During the election, Party leader Jagmeet Singh made repeated appeals to nationalistic themes, suggesting a shift in tone that aligns, even if subtly, with populist-nationalist undercurrents. Notably, Singh ultimately lost his seat and stepped down from party leadership—an outcome that raises questions about the political efficacy of adopting such rhetoric within a party traditionally aligned with internationalist, grassroots, and justice-oriented movements. A noteworthy example is found in an interview with the Toronto Star, where Singh relays, "To stop Pierre Poilievre, I put Canada before the NDP," a statement that underscores the prioritization of national identity over partisan loyalty (Toronto Star, 2025). This rhetoric was also present in a March 2025 post, captioned "Canada is not for sale. We're strong, and we'll never back down. #elbowsup," with text overlaid reading "Fight like hell for Canada" (Instagram). The framing positions Singh as a defender of Canadian values under threat, a narrative that mirrors nationalist tropes often employed by conservative leaders.

This messaging is further amplified on visual platforms. In a YouTube video, Singh declares, "Keep Canada, Canada," invoking themes of protectionism and national pride, and asserts it in different posts with variations of his line, "We are Canada. Strong. Proud. Free." (Instagram). A search through Singh's social media feed reveals a consistent emphasis on "Canada" as both a rhetorical and symbolic anchor in his more recent messaging (Twitter). These examples suggest that Singh is strategically engaging with a nationalist discourse, perhaps to counteract the populist appeal of his Conservative opponents while attempting to position the NDP as aligned with broader Canadian values and identity. This rhetorical shift reflects a broader trend in Western democracies where centre-left parties increasingly adopt patriotic or nationalist language—once considered the domain of the political right—as a way to reclaim national identity and counter far-right narratives.

A tweet from Singh claims that "Pierre Poilievre and the Conservatives fired 1,100 border officers in one day," leading to increased gun smuggling and making "Canadians… less safe" (Twitter). While this appears to be a straightforward critique of Conservative austerity and public safety policy, it operates as a subtle nationalist dog whistle. By invoking the border as a point of vulnerability and linking reduced border enforcement to threats from gun smuggling, the message draws on securitized narratives typically associated with right-wing populism. These narratives frame national borders not just as administrative boundaries but as symbolic front lines against chaos, crime, and foreign danger—rhetoric often used to justify surveillance, xenophobia, and exclusionary policies (Mountz, 2010; Anderson, 2013).

Singh's tweet implicitly constructs a Canada under siege. It casts the NDP as its defender, signalling a rhetorical shift in which even centre-left actors adopt the logics of national security and territorial sovereignty to assert moral and political authority. This mirrors broader trends in Western democracies, where centre-left parties—facing rising right-wing populism—have increasingly adopted language that emphasizes law and order, national safety, and border integrity to maintain credibility among anxious electorates (Moffitt, 2016; Kenny, 2021).

Singh was not alone. Many caught Canada fever. One would go to the grocery store and be inundated with maple leafs and variations of marketing around products being "Canadian-made."

Singh's rhetoric demonstrates a form of emotive and symbolic statecraft wherein national security and border control become sites for constructing political legitimacy. In adopting tropes usually associated with right-wing populism—such as crime at the border and threats to Canadian safety—Singh participates in a broader shift wherein even centre-left leaders use nationalist cues to assert political authority and electoral viability.

Many are typically able to hold rigorous positions that are not rooted in belonging to a Canadian nation-state and fueling affective statecraft.

People who typically engage in land acknowledgements, express concern for undocumented people, and refer to themselves as "guests on stolen land" suddenly have been caught in the fervor or nationalism, posting like proud patriots. The Canadian flag — once a symbol many progressive people viewed with caution — has re-emerged in their posts and profiles. The satirical outlet Walking Eagle News headlined, "Indigenous Person Unsure if House with Canadian Flag in Window Belongs to` Freedom Convoy Supporter or Liberal" — capturing the unease many felt around the flag's evolving symbolism.

Since the 2022 Freedom Convoy, the flag has taken on new meaning, often signalling a form of conservative nationalism that is increasingly xenophobic. Even before the convoy, during the height of the Black Lives Matter protests and after the murder of George Floyd, some police officers and Canadians began dawning a version of the flag with a thin blue line — a contentious symbol widely seen as emblematic of systemic racism and a divisive "us versus them" mentality. This same symbol appeared throughout the Freedom Convoy protests, linking both versions of the flag to right-wing ideologies. In response, several Canadian police forces, including the RCMP, Ottawa Police, and Vancouver Police, banned officers from displaying the Thin Blue Line imagery while on duty, citing its erosion of public trust. And yet, since Trump's rise in the U.S. and more recently in Canada's last federal election, many people — including self-identified progressives — have embraced a version of Canadian patriotism that appears to contradict the very anti-colonial, anti-racist values they claim to uphold. The national flag is clearly a rallying point for a growing form of reactionary nationalism; why, then, would anyone claiming to be on the left rally around it as well?

This resurgence of patriotic symbolism among liberals and progressives reflects a more profound discomfort with ambiguity — a desire for a clear moral high ground, even if it means embracing symbols that have long been contested. The flag becomes a shorthand for "decency," "order," or "stability," even as it carries with it the legacies of residential schools, exclusionary immigration policies, police brutality, and ongoing colonial violence. In moments of national crisis — whether a global pandemic, an election, or international conflict — people reach for unifying images. But the Canadian flag is not neutral. Its red and white threads are stitched through with contradiction: multiculturalism and genocide, hospitality and detention, healthcare and hunger, a peaceful Canada that provides arms to a settler colony, a flag that is emblematic of a settler colony through and through.

What's revealing is how quickly people who once critiqued settler nationalism fall into patriotic performance when their sense of Canada feels threatened — not by injustice, but by the possibility of political instability or association with American-style right-wing extremism. This is not unlike the liberal embrace of military flyovers or the quick pivot to "we're all in this together" messaging during COVID — moments where nationalism gets sanitized and rebranded as compassion. This rebranding creates a hard facade to penetrate and have honest, necessary conversations.

For many Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities, the flag has not been a symbol of safety or unity. Its sudden reappearance in progressive spaces doesn't just feel out of place — it feels like erasure. It flattens the complex, painful relationships many have with the Canadian state, reducing decades of resistance and refusal to embrace a hashtag moment or a window decal.

This contradiction becomes even more stark when we consider how Indigenous communities have long used the Canadian flag not as a celebration but as a canvas of critique — of mourning, resistance, and refusal. In 2013, Colby Tootoosis carried an upside-down Canadian flag into the grand entry of a powwow, a direct intervention that sparked public backlash and police involvement. Tootoosis's act was not just a rejection of the flag's authority but a ceremonial reframing, turning a symbol of occupation into one of active distress and truth-telling. Similarly, artist Teresa Marshall's Elitekey (shown at the National Gallery of Canada's Land, Spirit, Power exhibition) placed a half-raised Canadian flag — with its maple leaf cut out — next to a figure in traditional dress with no visible body. Between them, a canoe symbolizes both hope and betrayal. The absence of the maple leaf and the fragmented bodies spoke to the violence of erasure, particularly in the wake of the 1990 Oka Crisis, where the Canadian military confronted the Mohawk Nation.

In other instances, the flag has been used to underscore specific national failures. Artist Karen Cummings' textile work, "Someone Knows," exhibited at the Okanagan Art Gallery, reimagines the Canadian flag using reclaimed fabrics. Its iconic white stripe is replaced with 122 quilted squares — each stitched with either a red thread question mark or the outline of a body — memorializing the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). Cummings forces viewers to confront how national identity is built on disappearance — not just of land, but of life.

These artistic and political acts push back on the sanitized nationalism that has resurged in recent years. They remind us that for many Indigenous people, the flag is not neutral — and never has been. It is a signal not of pride but of pain. And it is through its alteration, its defacement, or its reimagining that a more honest story of this land emerges.

There is a tension that exists where the act of voting is often framed as a core civic duty and a meaningful expression of political will; it's important to interrogate what voting alone can actually achieve—particularly in a moment marked by resurging nationalist sentiment. It is also necessary to remember that voting has not always been granted to all, even in the 2025 Federal election Nunavik had polling stations that opened late or not at all, highlight ongoing systemic barriers that disenfranchise Indigenous communities in Canada. Despite constitutional rights to participate in elections, logistical failures and lack of culturally responsive planning continue to undermine equitable access to the ballot box.

Despite the progressive rhetoric that characterized the previous political era, this election cycle revealed how easily such language can be co-opted or abandoned in favor of more exclusionary, regressive platforms. This dissonance between campaign promises and political outcomes underscores the limitations of voting as a tool for genuine change. It's not that voting is meaningless, but rather that its power is constrained when systemic issues—like nationalism, white supremacy, and economic inequality—remain unaddressed by those in power, regardless of party.

Mood Management is not Liberation - Against Political Cosplay

Here, I'm thinking of the many thinkers, peers, and lived experiences that have shaped my politics. One is Glen Sean Coulthard, who writes:

I hold this position in direct tension with those who enthusiastically support a Liberal or Social Democratic incumbent simply because they have signed a pledge or made a gesture toward progressive values. The reality remains: the Liberal Party has failed to end long-standing boil-water advisories and has made limited progress on the 94 Calls to Action outlined by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I go back to Rudy's call on us to be Accomplices not Allies.

As Patrick Wolfe reminds us:

"Settler colonizers come to stay: invasion is a structure not an event. In its positive aspect, elimination is an organizing principle of settler-colonial society rather than a one-off (and superseded) occurrence." (from: Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native)

In Red Skin, White Masks, Coulthard pushes this further, reminding us that this is not only about political theory — it's a call to action:

"For Indigenous nations to live, capitalism must die. And for capitalism to die, we must actively participate in Indigenous alternatives to it."

So yes, vote — but do so with clarity. Know what you are doing, and just as importantly, know what you are not doing. Liberation does not happen at the ballot box. Use precise language. Do not let words drift and mutate into comfort — the act of voting is not more than it is, and we do ourselves a disservice when we pretend otherwise.

Fight against radical concepts and language that travel and mutate to self-soothe people who want the act of voting to be bigger or better than it is.

This contradiction isn't just about inconsistency — it reveals how hollow politics can become when divorced from sustained commitment. It's political cosplay: one day urging others to "vote like our lives depend on it," and the next day posting excerpts from Black Power or Pedagogy of the Oppressed, as if quoting radical theory can retroactively cleanse complicity with the status quo. The popular resurgence of a Kwame Ture quote this election — "You vote once in four years, and that's your political responsibility? That's the height of bourgeois propaganda…" — is a case in point. Too often, it's shared not as a provocation toward deeper organizing but as an aesthetic flourish—a kind of moral branding after a candidate someone liked has tanked or disappointed them.

In these moments, radical Black voices become content. The whole context of Ture's work — his deep critique of U.S. imperialism, his commitment to revolutionary struggle, and his rejection of liberalism — is flattened into a caption-friendly quip. This extraction is itself a kind of violence: the rebranding of revolutionary figures into mascots of the type of politics that ultimately reinforces the very systems they fought against. Just as the Canadian flag gets sanitized and reclaimed in moments of national insecurity, so too do radical legacies get reappropriated in moments of personal or collective political doubt — offered not as calls to action but as symbols of edgy self-awareness.

This isn't accountability — it's mood management. And it allows progressives to feel temporarily radical without risking anything: not their safety, not their relationships to power, and certainly not their national mythologies.

Not to the State, But to Each Other – What We Owe to Each Other

A few weeks ago, I reflected on my strong belief that voting is not harm reduction, nor is it apathy. It is a refusal to romanticize the mechanisms of empire and settler governance. It is a call to think beyond survival tactics that reinforce the status quo — the kind of survival that asks us only to endure, to minimize harm without ever confronting its root causes. This kind of survival keeps us trapped in cycles of compliance, asking only for less violence rather than imagining a world without it. The future we need will not be voted in; a statement from a government finally condemning genocide will not suffice.

During the 2016, 2020, and 2024 U.S. Presidential election cycles, a refrain echoed in certain activist and liberal idpol circles was: "We don't owe each other votes" or also "I don't owe people education." At first glance, this stance might seem like a call for respecting individual political autonomy or valuing disproportionate labour. But too often, it carried a condescending undertone—one that shut down collective accountability and erased the complexities of political solidarity.It was a refusal to engage with the sometimes uncomfortable work of building trust, sharing knowledge, and mobilizing communities together. The frameworks of refusing dialogue, shutting down questions, and framing relational and political work as burdensome are one that keeps us stagnant.

This attitude functioned as a kind of gatekeeping, a way to declare moral independence while simultaneously dismissing the very relationships that underpin effective activism and organizing.

By morally positioning certain level-of-education statuses as ones where you do not have to share knowledge, or see vote-sharing as debts to be withheld. These votes could translate into tangible rights for the most marginalized (think about those who smugly would not vote for Bernie Sanders and, by extension, universal healthcare in primaries because they wanted identity politics-based representation vis a vis a woman the majority of women cannot relate to but a professional managerial class of university-educated women could in Hillary Clinton, Elizabeth Warren, and Kamala Harris).

This stance resonated especially within a certain stream of Western, liberal-centric feminism that values self-preservation over collective responsibility and empowerment through personal choice over structural change. Here, refusal is stylized as resistance, and disengagement is misread as a radical boundary. But this form of politics rarely threatens power—it just recasts it in more palatable, individualized terms.

I do not dwell on this because it is one particular moment; I look at it as one version of paradoxically reinforced isolation and fragmented movements that occur in different iterations again and again. Rather than fostering spaces of mutual support, it produces a brittle individualism cloaked in the language of empowerment and identity—one that ultimately limits the imagination of what political responsibility can be.

For those who do vote — who feel a duty, a desperation, or a pressure to do so — that act cannot end at the ballot box. If voting is a tactic, it cannot become one's politics. Our politics must live elsewhere: in our communities, in our solidarities, in our refusals, in our visions. We must not confuse access to participation (arguably an act that does not render muchchange in Canada) with liberation itself.

To vote and do little after is to allow empire to frame the limits of your responsibility. It is to be pulled into its rhythms, its symbols, its ritual performances of change. For those who vote or who organize in electoral contexts, there remains an unshakable obligation — not to parties, not to politicians, not to the myths of representation — but to the people at the doors you canvass. To honour the word you gave people at the doors of their homes.

Our accountability is not just to abstract notions but to real people and real histories. We carry obligations to honour the lineages of resistance we come from and/or the politics we espouse. To honour our communities and communities we allegedly advocate for, especially those for whom voting was never an option — whether by law, design, or geography. To honour the land we stand on and those still fighting for its return.

Voting must be understood as an act bound by deep responsibility. The work does not end with a ballot. It only begins. We are responsible for what comes after — for staying vigilant, for telling the truth, for refusing to disappear the violence of the state when it is dressed in our chosen colors, in our ignoble flags.

For one, voting is not an exercise in power. In Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition,Glen Coulthard argues that as long as recognition is something granted by a dominant power to the oppressed, it cannot be a path to liberation. Recognition, in this model, is not mutual or reciprocal — it is conditional. It is always filtered through the lens of the settler state, which maintains the authority to validate or deny the legitimacy of Indigenous presence, culture, and governance; this concept can be extended, especially in this political moment.

This same logic is at play in electoral politics. Voting, as structured within a settler-colonial state, often masquerades as empowerment while reinforcing the very systems that disenfranchise. When participation is framed as recognition — when the state invites historically oppressed peoples to engage on its terms through its institutions — that participation becomes another form of containment. It binds our political imagination to the parameters of legitimacy defined by empire. Last year, I recall reading a tweet that cut through the noise: "Your voting fetish is limiting your imagination." That line was not just clever, but clarifying. This is a reminder that real political engagement begins where sanctioned participation ends.

As Coulthard notes, this model entrenches "the assumption that the flourishing of Indigenous peoples as distinct and self-determining entities is significantly dependent on their being afforded cultural recognition and institutional accommodation by the settler state apparatus." In other words, liberation is made contingent on recognition from the very system that suppresses it.

Applied to elections, this means that inclusion in the vote is not the same as inclusion in power — and certainly not in justice. It keeps us locked into the logic that our self-determination must be validated by a ballot, that our future is dependent on political cycles, and that freedom is something we can lobby for rather than something we must assert and build outside the terms of settler governance.

To vote within such a system can be strategic, but it is not emancipatory on its own. It must be accompanied by a refusal to mistake recognition for liberation and a commitment to building power and solidarity beyond the ballot box — in our communities, in our movements, and in the relationships to which we are accountable. Otherwise, we risk mistaking visibility for freedom and participation for transformation.

Audre Lorde reminded us that "the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house." That means we must not be seduced by the idea that justice can be brokered within the architecture of the carceral state, the settler state, and the imperial state. These tools may rearrange power temporarily. They may offer a short-term reprieve. But they will not free us. And they were never meant to.

When we pretend otherwise, we betray the people who cannot afford our illusions. We betray those who live at the sharpest edges of the systems we try to reform. We betray those whose futures will not be protected by legislation but by resistance.

I fear a future where harm reduction, abolition, and community care become corporate language. Where mutual aid is funded by the same governments that withhold welfare. Where liberation frameworks are absorbed into electoral platforms and sold back to us as policy. Where decolonization becomes a metaphor instead of a demand.

Voting, especially in that context, becomes a tool of pacification — a strategy of co-optation. And yet, some of us will still vote. So, if we do, we must carry the weight of that choice with integrity. We must refuse to let it soften our tongues or dull our analysis.

We owe nothing to the state, but everything to each other. To the people who are still under siege, who are still locked up, who are still mourning, who are still resisting. Our solidarity must be fierce and unswerving, even — especially — when it is unpopular.

We do not want inclusion. We want transformation. We do not want representation in violent systems. We want to end those systems. The futures we imagine cannot be legislated into existence. They must be built. And they will be — not by politicians, but by people who have the courage to name the truth and the commitment to live by it.

These obligations cannot be cast on a ballot and never will be. It must be carried in our hands, in our actions, in our refusal to be silenced or softened.

This is one of the responsibilities we must carry after. Not to the state. Not to the spectacle. But to each other.

Towards and for the unfinished work of liberation. To futures, we may never see, but we must still protect.

Voting, as above mentioned in this way and within the current context, becomes revealed as a tool of pacification and a strategy of co-optation.

And yet, some of us will still vote.

If we do or you do, we must carry the weight of that choice with integrity. We must refuse to let it soften our tongues or dull our analysis.

We must keep speaking about Palestine.

About Black liberation.

About Indigenous sovereignty.

About disability justice.

About the worlds we are trying to build — not manage and ask for accommodations.

Because what we owe is not to the state but to each other.

Vote Out Loud, No Quiet Ballots

Witnessing the results of the 2025 election, it's clear that many voted against Poilievre rather than for a particular vision.The anti-conservative sentiment ran so deep that the NDP lost party status — a historic blow. In riding after riding, traditional NDP voters went red.

There's a recurring opinion among organizers that it can be easier to build resistance when the opponent is clearly defined — the "devil you know" logic. I agree; since the election, I've found myself in rooms and conversations with people who claim to hold pro-labour, anti-war, New Democrat values — and who nonetheless voted Liberal.

This dissonance was strikingly reflected in a recent Stripper News video, where two individuals awkwardly stumbled from expressing concern for Palestine to justifying their Liberal vote on the basis of personal interest.

What we're seeing is a pattern of secretive, conflicted voting — the kind that explains how the Liberals, polling at 20% just weeks before, managed to leap to nearly 40%, securing a best-scenario minority government that looks and acts dangerously close to a majority.

This is the tension of the quiet ballot — unspoken, unaccountable, and yet with very loud consequences.

Human rights attorney, scholar, and author of Justice For Some Noura Erakat addressed this same tension during the 2024 American election.

"Progressives voting Harris need to be public about it & include some sort of pledge to disrupt the system (resign en masse, go on strike…) if she doesn't deliver embargo, ceasefire in first 100 days.

Secretly voting 4 'better organizing conditions' w/o an imperative is inadequate.

Doing it to 'avoid things getting worse' pretends like it's not already the worst for Palestinians enduring annihilation — and for those of us racialized in the U.S. as terrorists, enemies of the state, sleeper cells, enduring violence, doxxing, loss of employment, deportation.

So, if voting for Harris is your position — own it loudly and connect it to your self-imposed accountability.

Make a pledge — don't vote and disappear. Vote, take the front line, and sacrifice — make good on your theory of change."

We can carry the same principle here.

If we vote, it must not be quiet.

It must not be secretive or ashamed.

It must be accompanied by a public, visible, unrelenting commitment

to act, to refuse, to disrupt, to honour our solidarities.

Because what we owe is not to the state but to each other.

Politics is every day. It's not just a vote or sharing a quote over an image in a 24-hour story. It's the slow, continuous, often uncomfortable work of unlearning, connecting, and resisting — not in the name of branding or taking a selfie with a vote sign, but of liberation.

Otherwise, we risk laundering our participation into complicity.'

Big gratitude to Kalden and Nabeela for being extra eyes and ears, humouring all of my ideas and thoughts I want to unravel in words.

Some Works Referred to:

Anderson, B. (2013). Us and Them? The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Control. Oxford University Press.

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. University of Minnesota Press.

Mountz, A. (2010). Seeking Asylum: Human Smuggling and Bureaucracy at the Border. University of Minnesota Press.

Moffitt, B. (2016). The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford University Press.

Kenny, M. (2021). "The rise of progressive patriotism in British politics." The Political Quarterly, 92(2), 178–185.

Rudy. (2014) https://www.indigenousaction.org/accomplices-not-allies-abolishing-the-ally-industrial-complex/

Salaita, S. (2024, May 4). Care and carefulness in today's United States. https://stevesalaita.com/care-and-carefulness-in-todays-united-states

Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), 387–409.https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240

Production Credits:

Written by Nashwa Lina Khan

Production by Nashwa Lina Khan and Andre Goulet

Essay Editing by Kalden Dhatsenpa and Nabeela Jivraj

Social Media & Support:

🎧 Listen Now: Wherever you get your podcasts! (spotify/apple)

📬 Subscribe: Habibti Please Substack

🐦 Follow Habibti Please on Twitter: Habibti Please

🐦 Follow Nashwa Lina Khan on Twitter: Nashwa on twitter

🌳Our Linktree

💕Habibti Please is proud to be part of the Harbinger Media Network